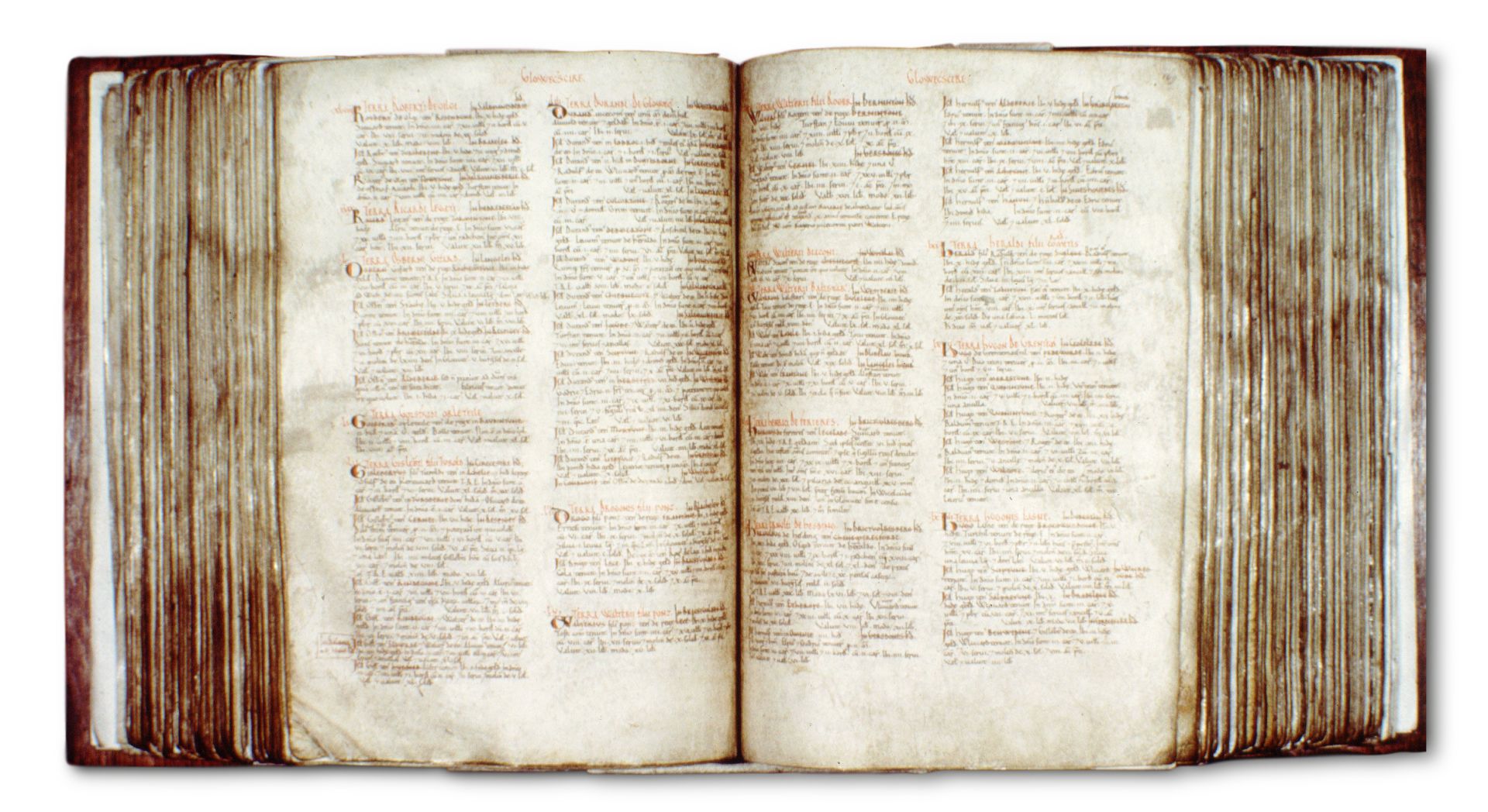

The precise purpose of the enterprise is not known but the most likely reason was to determine who legally owned what land, to settle disputes of ownership and to measure income, particularly agricultural income, in order to apply a future tax.

#Doomsday book full

The record is unique in European history and, packed full of statistics and snippets which reveal details of medieval life in England.ĭomesday Book was a comprehensive survey and record of all the landowners, property, tenants and serfs of medieval Norman England which was compiled in 1086-7 CE under the orders of William the Conqueror (r.

Compiled in 1086-7 CE by William the Conqueror as a survey of land and property ownership across Norman England. For these three counties the full, unabbreviated return sent in to Winchester by the commissioners is preserved in the second volume (Little Domesday), which, for some reason, was never summarized and added to the larger volume.Ĭontaining 413 pages, it is currently housed in a specially made chest at London’s Public Record Office in Kew, London.Domesday Book is actually composed of two volumes, with here shown the larger of the two, the Great Domesday book.

The first volume (Great Domesday) contains the final summarized record of all the counties surveyed except Essex, Norfolk, and Suffolk. The Domesday Book is actually not one book but two. The name ‘Domesday Book’ was not adopted until the late 12th Century. This led the book to be compared to the Last Judgement, or ‘Doomsday’, described in the Bible, when the deeds of Christians written in the Book of Life were to be placed before God for judgement. Indeed, it was noted by an observer of the survey that “there was no single hide nor a yard of land, nor indeed one ox nor one cow nor one pig which was left out”. It acquired the name ‘Domesday Book’ because of the huge amount of information that was contained in it. Brighton residents may enjoy fishing but how many catch enough to pay their taxes? The Domesday Book reveals that one Brighton landowner did exactly that – with 4,000 herrings to be precise! Once they returned to London the information was combined with earlier records, from both before and after the Conquest, and was then entered, in Latin, into the final Domesday Book.Īs well as valuing assets, this fascinating document gives a valuable insight into land use at the time, the life of local landowners, and even disputes between neighbours.īy studying individual entries it is possible to discover that upmarket Hampstead in London had woodland containing 100 pigs and was assessed as being worth 50 shillings. They carried with them a set of questions and put these to a jury of representatives – made up of barons and villagers alike – from each county. The country was split up into 7 regions, or ‘circuits’, with 3 or 4 commissioners being assigned to each.

The information in the survey was collected by Royal commissioners who were sent out around England. This survey was also needed to asses the state of the country’s economy in the aftermath of the Conquest and the unrest that followed it.įirst published in 1086, it contains records for 13,418 settlements in the English counties south of the rivers Ribble and Tees (the border with Scotland at the time). William needed to raise taxes to pay for his army and so a survey was set in motion to assess the wealth and and assets of his subjects throughout the land. Residents of Hampstead might not be too pleased to learn that their exclusive London village once housed more pigs than people but this is just one of the fascinating insights to be gained from reading the Domesday Book.Īfter the Norman invasion and conquest of England in 1066, the Domesday Book was commissioned in December 1085 by order of William The Conqueror.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)